Should You Be Blocking ChatGPT’s Web Crawler? CNN, Disney, Reuters, and the New York Times Already Are

The emergence of generative AI tools, like OpenAI's ChatGPT and Google's Bard, has sparked much excitement. Yet, many publishers are concerned about the use of their valuable content to "train" these learning models without permission or compensation. For healthcare and higher education publishers, navigating the strategic pros and cons of blocking these tools can be particularly challenging.

ChatGPT’s ability to converse knowledgeably about any topic imaginable is undeniably impressive. Captivating the world, it has transformed tasks from writing to coding and helped the site reach 100 million monthly active users in January, two months after its launch. That makes it the fastest-growing consumer application in history and the source of a $29B valuation for OpenAI, ChatGPT’s parent company.

But, a dark side to ChatGPT’s trajectory is emerging. We’re now learning that much of the “training” of its generative AI models has been done without the permission of the publishers whose websites its crawlers periodically scan. Google’s been doing much the same.

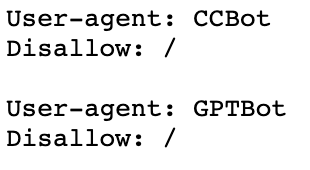

That’s a big problem, say CNN, Disney, Reuters, the New York Times, and others. They’re asserting copyright-based control of their text, video, and graphic content by blocking GPTBot, the web crawler used by ChatGPT. They argue that their content has immense commercial value and that its use requires both permission and compensation. Several have blocked all crawlers associated with AI technology.

“Because intellectual property is the lifeblood of our business, it is imperative that we protect the copyright of our content,” noted a Reuters spokeswoman.

News Corp’s CEO Robert Thomson agrees, arguing that the “[media’s] collective IP is under threat and for which we should argue vociferously for compensation.”

News outlets aren’t the only ones, either. Popular sites like Amazon, Indeed, Quora, and Lonely Planet have also blocked the GPTBot crawler.

OpenAI and others reject this thinking. They acknowledge that their crawlers learn from what they find online, but argue that their language models go on to completely synthesize and transform these publicly available inputs — essentially creating something new to the world. Traditional copyright rules don’t apply here, they’d have us believe.

So, what might all this mean for academic publishers, namely colleges, universities, teaching hospitals, research centers, and the like? Let’s think it through.

On the one hand, some see academic content as an organizational asset, one to be vigorously protected from unauthorized use. It’s expensive to create and it may also be integral to a researcher’s career or an organization’s external brand. That’s why most organizations copyright anything they share with the public. Protecting your investment from ChatGPT and others should be an urgent priority, no?

As you might expect, it’s not that easy.

Imagine a hospital or college blocking ChatGPT’s crawler and then discovering that they no longer can influence its results for even basic factual inquiries — a doctor’s research, for instance, or a summary of student aid offerings. Absent reliable source content, ChatGPT may well rely on incorrect or incomplete information from third-party sources. That’s a potential risk to your brand and your patient or student experience.

There’s another problem too. Research-oriented academics and their organizations publish in large part because they want to have an impact. Impact requires an audience who can find and read your thinking. Here’s the dilemma: blocking ChatGPT and other AI crawlers effectively makes your content invisible (and likely irrelevant) to hundreds of millions of curious users. If your goal is to influence the public’s dialogue, you’ve failed — protecting your investment has paradoxically damaged it.

Amanda Todorovich, a senior marketer at Cleveland Clinic who oversees their highly regarded publishing efforts, is amongst those seeking a solution.

“It’s a difficult situation. While we absolutely want to protect our investment in content and publishing, we also need to be a part of the answers people receive when using these tools to make healthcare decisions. No matter what, our mission is to help people take care of themselves and their families,” she observes. “This is a daily conversation with my team, legal, and other stakeholders right now. No easy solution.”

Brian Piper, an author, speaker, and content strategist at the University of Rochester agrees — and makes an important point about attribution. “As an academic institution, we create content to increase brand awareness and promote our world-class research and innovative education. These Large Language Models (LLMs) are here to stay and we need to figure out how to integrate them into our discoverability strategy."

Brian continues, "Search engines are experimenting with Search Generative Experiences (SGE) and are beginning to give attribution for the sources of their information in many cases and I think we’ll see more of that in other generative AI tools. By allowing AI tools to scrape our sites, we not only augment our brand recognition through cited references but also contribute to developing more precise and informative models. In doing so, we can collectively elevate the quality of information accessible to users, making it a win-win for everyone involved.”

If you’re part of an academic publishing team — a college, university, or academic medical center — I'd love to hear your thoughts. How will you navigate these uncharted waters? Is there a solution out there that will work for everyone? I’ll be watching this closely and hope you will too.